A bad Stoic's take on the Dichotomy of Control

Hi I’m Yihwan, and I’m a bad Stoic.

I study Stoicism, but I’m not much of a Stoic scholar. I can’t say what Seneca meant or Marcus Aurelius intended, especially since I haven’t made it through all of Seneca’s letters (he wrote a lot!) or read Meditations cover-to-cover.

But over the years, Stoicism has helped me prioritize my daily work, focus on what’s most important in life, and even find a bit of inner peace. Of all the Stoic teachings, the Dichotomy of Control has been the most impactful.

The Dichotomy of Control

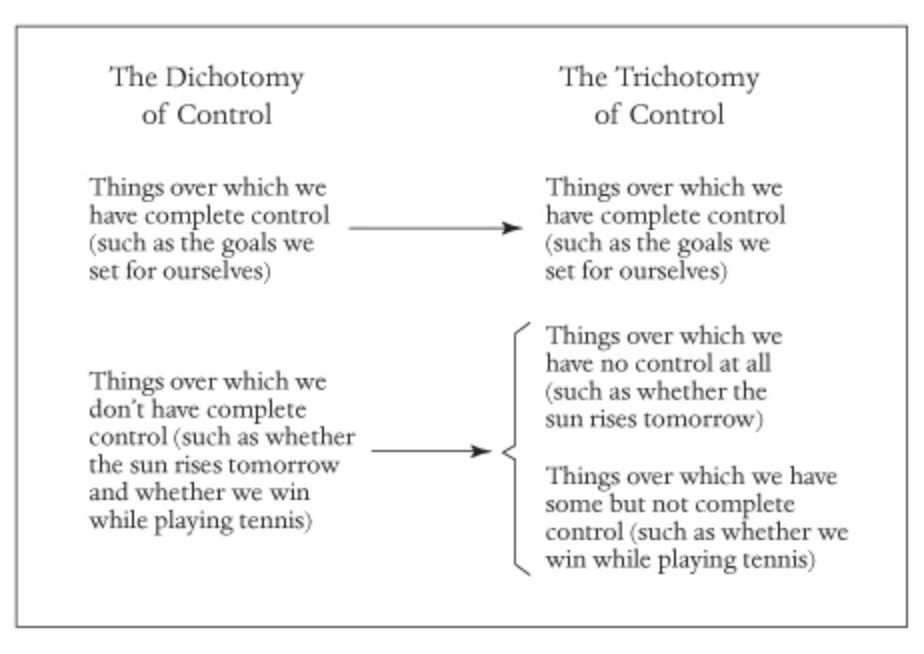

At its core, the Dichotomy of Control is about separating things you can control (internal things) from things you can’t control (external things) — and not worrying about the latter. In other words, focus on yourself — and the things you alone can control.1

The basic tenet seems straightforward enough. If you can’t control something, why worry about it? It’d be like worrying whether the planet stops spinning tomorrow — a bit silly, and not worth your time.

But as someone who likes to frame situations in terms of probabilities, I find a strict Dichotomy of Control somewhat unsatisfying. After all, there might be things you have complete control over (whether you check your phone right after waking up) and things you have no control over (whether the planet stops spinning tomorrow), but surely there must also be things we can partially control. Should we completely discount those as well?

The Trichotomy of Control

Enter the Trichotomy of Control, proposed by William B. Irvine in The Guide to a Good Life.2

The Trichotomy of Control provides an escape hatch from a strict Dichotomy of Control (“things over which we have complete control” versus “things over which we do not have complete control”) by explicitly adding a third category: things over which we have some, but not complete control.

To illustrate his point, Irvine suggests that we have some, but not complete control over winning a tennis match. In this example, Irvine advises us to separate external goals (whether we actually win) from internal goals (whether we play to the best of our ability) to maintain our inner tranquility. By focusing on an internal goal we can control, we lessen our chances of being upset by the actual outcome of the match.

But Donald Robertson, author of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, expresses skepticism:

Irvine seeks to replace the Stoic dichotomy between things under our control (or “up to us”) and things not, with a “trichotomy” that classifies most events in a third category, consisting of things “partially” under our control … this would seem to wreck the conceptual framework of Stoic Ethics … It would be better to spell out which parts or aspects of a situation are within our control and which are not, and that inevitably brings us back to the traditional Stoic dichotomy. [emphasis added]

While I can’t comment on how a Trichotomy of Control might “wreck the conceptual framework of Stoic Ethics,” I’m intrigued by Robertson’s suggestion that we think harder about “which aspects of a situation are within our control and which are not” to bring us back to a traditional Dichotomy of Control.

“Segment, segment, segment”

Back when I worked in consulting, I was told that the first step to solving any problem was to “segment, segment, segment” until I identified the real underlying issue. Engineers often take a similar approach to breaking down larger problems into smaller, more manageable pieces.

As an (admittedly contrived) example, here’s a common consulting case interview question:

Profits are down 40% this year. What do we do?

The correct answer is not, as I did, to start sweating through your new suit and frantically searching for the nearest exit. Instead, the idea is that you ask exploratory questions to segment the problem until you arrive at the root cause.

So a better answer might follow this typical framework:

Profit is income minus expenses, so you ask whether income or expenses have changed.

If income has remained stable but expenses have increased, you know this is a cost problem. So you start asking about how costs have changed over time across different categories.

You continue to drill-down into each category, sub-category, and sub-sub-category until you can confidently say that the copy machine in the third floor break room of the Midtown office has been jammed since last February — and that is why profits are down 40% this year.

Segmenting down to a Dichotomy of Control

To bring this back to Irvine’s tennis match, “playing to the best of my ability” doesn’t seem like an ideal goal because it’s too ambiguous. What does “best” mean? Best compared to what? My previous efforts? Most crucially, how would I actually know if I had played my best or not?

The original goal was winning a tennis match, which most Stoics would probably agree is a not great goal because the outcome largely depends on external factors outside our control.

Irvine proposes a more inward-facing goal of playing to the best of your ability or trying your best. This is better, but could probably be segmented further.

Let’s consider the elements of a tennis match over which you have the most control. As someone who used to play a lifetime ago, the first thing that comes to mind is the initial serve for each point. Actually attempting a serve (and getting it in) has nothing to do with your opponent, so this seems a natural candidate for a goal we have more control over.

However, a reasonable critic could argue that getting your serves in is still outside your control. Gravity, wind speed, and any number of external forces could affect whether your serve spins satisfyingly into the service box — or flies far past no man’s land.3

Perhaps when thinking about goals, we could focus more on our actions than the actual outcomes. While getting your serve in represents an outcome, actually attempting a serve represents an action. Since we have complete control over our actions, this seems a step in the right direction.

We could also stop here, because we’ve technically found a Dichotomy of Control. We could either attempt a serve or not attempt a serve. But to me, “attempting a serve” feels like an underwhelming goal, especially when compared to the original goal of winning the match.

In order to align our actions with greater goals, we could focus on practicing your serves to get better at them. We could make this goal even more actionable by adding concrete details such as practicing your serves every other day for one hour. You could either choose to practice — or not. We still have our Dichotomy of Control, but with a greater focus on improving our game over time.4

Serving is just one part — in fact, the first part — of playing tennis. There are obviously many other parts: returning the serve, running to meet the ball, volleying accurately, timing your overheads, and so on. Each part can be segmented into its own sub-parts, but the unifying theme is that you alone decide to practice consistently — or not. Showing up to hone your skills, day in and day out, is completely within your control.

By the time the match rolls around, it’s not about winning — or even “trying your best.” You’ve already put in the work and done everything you can to prepare for the match before it even begins. This realization, along with the acceptance that the actual outcome of the match is outside your control, can be freeing — a feeling some refer to as finding their inner peace and tranquility.

Beyond tennis

We’ve run with Irvine’s tennis example this far, but segmenting down to a true Dichotomy of Control can have broad applications to all aspects of life: getting a raise or promotion, starting a company, meeting new friends, or whatever else you’d like to do.

Attaining your goals will rarely be completely within your control, but that doesn’t mean they’re not worth pursuing. Instead glossing over things you can only “partially” control through a Trichotomy of Control, see if you can segment further. More often than not, you can probably arrive at a true Dichotomy of Control to more intentionally channel your attention and focus.

- You can find the source material for the Dichotomy of Control in Chapter 1 of the Handbook (or Enchiridion for anyone who speaks Greek) of Epictetus, though I personally find this simplified version to be less dense than most translations. ↩

- I highly recommend this book as a more accessible application of Stoic philosophy. ↩

- For me, the latter scenario tends to occur with embarrassing frequency. ↩

- Rigid adherents to Stoicism might protest that actual tennis-playing improvements remain outside our control. They would be right, of course. But that’s okay because we’re not debating philosophy; we’re playing tennis! ↩